At Healing for Gaza, we provide free, trauma-specialised mental healthcare to Palestinians affected by the ongoing genocide in Gaza. In just one year, our global network of clinicians and interpreters has delivered over 1,000 psychotherapy sessions, reached more than 500 people through field missions, and provided individualised care to over 100 patients — an impact made possible by our dedicated clinical coordination team.

Before sessions begin, each patient meets with the coordination team — Operations Manager and Clinical Coordinator, Aya Zakaria, and Clinical Coordination Assistant, Nadia Rdeini — who serve as the vital link between patients, clinicians, interpreters, supervisors, and field partners.

In this interview for Healing for Gaza’s blog, Aya and Nadia share what drew them to this work, how they keep the system running under pressure, and why clinical coordination is at the heart of Healing for Gaza’s innovative model of emergency mental health care.

Q: Tell us about your background and role as clinical coordinators. How has your experience prepared you for this work in Gaza’s volatile context?

Aya: I have nine years of experience in the humanitarian sector, including as Dr. Chen’s Executive Assistant and Lab Administrator, where I gained deep insight into complex scheduling, programme administration, and coordinating multiple moving parts. As a Clinical Coordinator, I oversee the therapy schedules for dozens of patients, ensuring the matches made during triage are carried through and that sessions run smoothly across multiple time zones.

Nadia: I’ve worked in the humanitarian sector for the past nine years with various non-profits, including an initiative I founded that delivers educational and arts programmes to young Syrian refugees in Lebanon. I also produce a podcast that provides divorced refugee women with a platform to share their stories and experiences. As a Clinical Coordination Assistant, I work closely with Aya to arrange therapy sessions, finalise appointments, and act as a bridge between patients, clinicians, and interpreters so communication flows smoothly and boundaries are maintained. I joined Healing for Gaza because I believe everyone has a mission in life, and mine is to help others. This is the first time I have been able to directly serve my own community, the Palestinian people, and that has been incredibly meaningful for me.

“This is the first time I have been able to directly serve my own community, the Palestinian people, and that has been incredibly meaningful for me.”

— Nadia Rdeini

A cornerstone of Healing for Gaza’s model is its secure coordination system, designed to ensure ethical care and protect patient confidentiality. At the heart of this process are our Palestinian clinical coordinators, who serve as the patient’s first point of contact before triage with Founder and Executive Director, Dr. Alexandra Chen. They are more than schedulers — they hold patients’ stories and emotional realities with care, acting as a “container” for the therapeutic relationship.

Q: What does it mean to be the ‘container’ between patient, clinician, and interpreter — and how do you protect confidentiality in that role?

Aya: Being a “container” means holding patients’ trust and safeguarding their stories. Sometimes they share deeply personal things — even in the middle of the night during moments of crisis — because they know we’ll support them. Once, a patient contacted me at 2 a.m. after a bomb shattered the window next door, covering her in glass. I stayed with her over messages until 4 a.m., helping her calm down. We act as the secure channel between patient, clinician, and interpreter, holding sensitive information until it’s appropriate to pass on. That trust is strengthened by our communications protocols: every patient is assigned a unique code instead of their name, personal contact details are removed, and names are deleted from secure messages once identification is confirmed. This keeps all exchanges focused on care, prevents off-hours or inappropriate contact with clinicians, and protects the integrity of the therapeutic relationship.

Nadia: We relay information securely, often translating if needed, before passing it on. Even calendar invites are anonymised so email addresses remain private. This centralised approach preserves privacy, safeguards professional boundaries, and ensures that sensitive information is handled with care. Without it, boundaries could blur, trust might be compromised, and the safe, neutral space we work so hard to create for patients could be lost. By building trust and guiding sensitive disclosures safely between patient, clinician, and interpreter, we create the conditions for ethical care, stability, and healing.

“Being a “container” means holding patients’ trust and safeguarding their stories… We act as the secure channel between patient, clinician, and interpreter, holding sensitive information until it’s appropriate to pass on.”

— Aya Zakaria

Equally important to confidentiality is the way Healing for Gaza safeguards boundaries in every therapeutic exchange. Our coordinators serve as the central communication hub, anonymising records, filtering messages, and protecting personal contact details such as phone numbers, emails, or social media accounts. All communication — whether it’s a message, a session update, or a cancellation — flows through the coordination team, then is relayed securely. By keeping all contact within structured channels, they maintain clear, compassionate boundaries that protect privacy, reduce the emotional burden on both patients and providers, and prevent burnout from off-hours support requests. Aya and Nadia also work in scheduled shifts with accrued rest hours to prevent burnout and protect their mental wellbeing. These safeguards are what make Healing for Gaza’s model distinct, ensuring that trust and care are sustained over time.

Q: Why is protecting boundaries between the patient, clinician, and interpreter so vital in your work?

Aya: Boundaries are what keep the therapeutic space safe for both patients and providers. In the context of Gaza — where people may be in crisis or living under extreme stress — even small breaches can quickly erode trust or create unhealthy dependency. Clear roles and structured communication ensure relationships stay professional and focused on healing.

Nadia: Boundaries also give patients the freedom to speak openly. If personal contact details or social media connections were exchanged, they might worry about being judged or misunderstood, and hold back from sharing important feelings. By keeping all interactions within secure, professional channels, we protect that openness and make sure every conversation stays centred on their care.

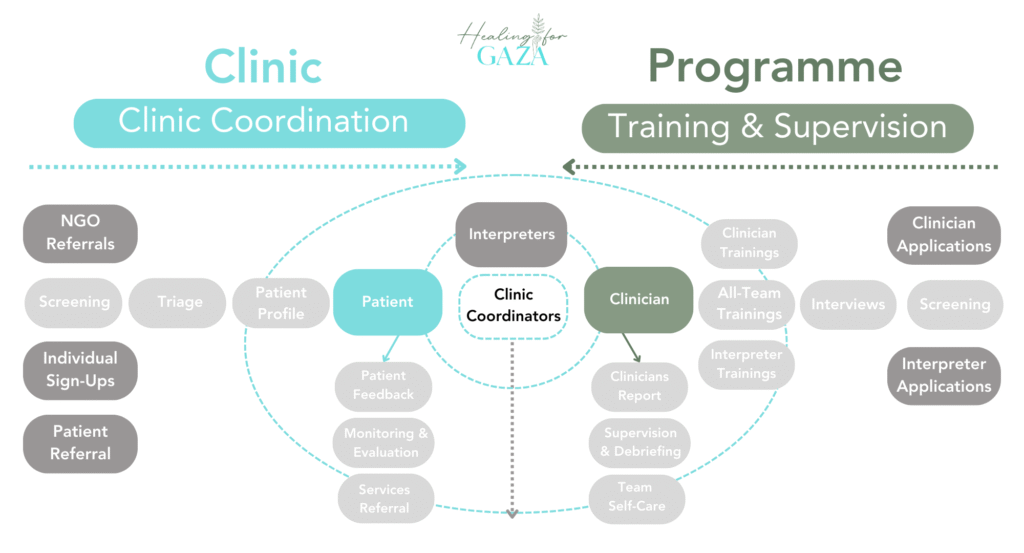

Our Clinic Coordinators sit at the centre of our HFG Operational Model, serving as a secure container for our patients, clinicians, and interpreters, bringing together the operations of both Clinic and Programme.

Trust is central to any humanitarian work, but it is especially critical in the sensitive, confidential space of clinical mental health. Aya and Nadia’s shared Palestinian identity helps them connect with patients quickly and deeply.

Q: What personal experiences or qualities help you build trust and strong connections with patients?

Nadia: Building trust takes work and strong communication skills. Aya and I are both Palestinian, so we approach this as if we’re supporting members of our own family. That shared identity helps us connect. We make sure our patients know we hear them, feel for them, and understand their struggles. When we speak with them, we do so as if we’re living their situation alongside them. In return, patients feel safe to speak openly, knowing we understand their struggles in ways others may not.

Aya: As a Palestinian, I feel joy in meeting other Palestinians around the world, and that shared identity builds trust naturally. For many, starting therapy can feel daunting, especially with someone they have no cultural connection to. Simply knowing I am Palestinian often helps patients feel more at ease and more willing to try. I remember one patient who was hesitant to start online sessions; after a few conversations, she agreed to try, and soon felt comfortable enough to continue.

Aya and Nadia supporting the training of Clinicians Cohort 5 via realistic role plays.

Because Healing for Gaza operates across dozens of cities and time zones, the clinical coordination team must constantly adapt. Power cuts, internet instability, and drastic time zone differences all pose challenges, yet therapy remains the one thing many patients look forward to each week. It is the coordinators’ job to make sure no session is lost, and that support continues no matter the circumstances.

Q: How do you troubleshoot when connectivity or logistics break down? What role does technology play in making therapy possible in Gaza’s context?

Aya: While it was simpler when our first cohort shared similar time zones, expansion to a global network — including clinicians in Australia with a 10+ hour difference — brought new challenges. Clinical coordinators go the extra mile to meet patients where they are, offering options like video, no video, phone calls, or messaging so they can choose what works best for their situation. With Gaza’s internet issues, not everyone’s phone is reachable, so I often find other ways to connect — through email or different platforms — so no one misses their session. It’s a task clinicians and interpreters often don’t have the bandwidth for, but it’s crucial because patients tell us therapy is the one thing they look forward to each week.

Nadia: We also connect patients with outside organisations to access essentials such as food, water, and shelter, because without stability in basic needs, therapy alone cannot be effective. Technology can be frustrating, but it’s also what makes this work possible. By being resourceful and persistent, we show patients that their care matters — that we’ll keep trying, no matter the barriers.

Beyond day-to-day coordination, Aya and Nadia also prepare clinicians and interpreters for the unique realities of working in Gaza. While our providers are highly experienced in trauma therapy, many have not treated patients living through active genocide. Role plays based on real cases help them understand the emotional weight, cultural nuances, and urgent realities of this context before they begin sessions.

Q: You also lead role plays for clinicians and interpreters. How do these sessions help prepare them to work effectively with patients in Gaza?

Aya: The role plays are based on real patients from Gaza, which means we often portray cases involving grief, loss, anger, dissociation, and depression in the context of ongoing genocide and displacement. Because we’re in direct contact with the patients, we have a deep understanding of their realities — not only their symptoms, but the environment they live in and the daily stressors they face. This allows us to embody their experiences authentically so clinicians and interpreters can grasp the emotional and cultural nuances, seeing us as the patient rather than just hearing a description.

Nadia: Exactly. We know our patients’ stories, struggles, and pain firsthand, so role playing gives us a way to bring those lived experiences into the room. It’s not about teaching qualified clinicians the basics of handling grief or trauma — it’s about grounding their work in the specific realities of Gaza, helping them understand how ongoing genocide, loss, and instability shape what the patient might be feeling in that moment.

“We know our patients’ stories, struggles, and pain firsthand, so role playing gives us a way to bring those lived experiences into the room.”

— Nadia Rdeini

Q: Nadia, in addition to leading role plays, you also coordinate Healing for Gaza’s monthly clinical supervision and debriefing groups. Why are these groups so important?

Nadia: After years in the field, I can say with certainty that what keeps staff from burning out — or harming themselves — is having a safe space to express what they’re feeling. Healing for Gaza is the only organisation I’ve worked with that has regular supervision groups, and they’re invaluable.

They provide accountability, help us check each other’s blind spots, and allow us to process trauma in ways that protect both our sessions and our personal wellbeing. Even the most experienced therapists need external support. Sadly, this isn’t standard practice in most organisations, but it should be — because without it, providers can carry trauma in dangerous ways. These sessions give clinicians and interpreters a place to release the tension from the heavy, often violent stories we hear.

Just as monthly supervision groups give clinicians and interpreters space to share honestly and feel supported, Healing for Gaza also creates regular opportunities for patients to voice their own experiences. Patient feedback is a vital part of strengthening our services, ensuring that therapy remains responsive, respectful, and rooted in their needs.

Q: What kinds of feedback do patients share with you about their experiences?

Aya: Every six weeks, we send patients a feedback form. So far, the responses have been overwhelmingly positive. Many message us to say they enjoy their therapy sessions and often thank us for giving them the opportunity to receive care.

Nadia: Patients often say they value having a safe space to speak without judgement, where they feel heard, understood, and supported. Many describe feeling forgotten before they began therapy, but even after one session, they often report a sense of relief and hope. One patient told me she never needs reminders about her appointments because therapy is the one thing she looks forward to each week. We’re also grateful that so many feel comfortable sharing feedback — and their progress — with us directly. The positive experiences have led many patients to refer family and friends to us. Demand is high, and we now have a long waiting list. Aya reviews and prioritises new cases based on urgency and need, with children receiving the highest priority.

The positive experiences have led many patients to refer family and friends to us. Demand is high, and we now have a long waiting list. Aya reviews and prioritises new cases based on urgency and need, with children receiving the highest priority.

Q: What have you learned from working so closely with patients navigating genocide, loss, and displacement?

Nadia: Our patients inspire me every day. Despite the violence and devastation they face, they remain ambitious — pursuing education, following their dreams, and seeking to improve themselves. They remind me how vital our shared humanity is. The people of Gaza are full of life, even in the harshest circumstances, and the world could learn so much from them.

Aya: I feel the same. Even with everything they endure and witness, they still want to learn. Some ask about scholarships abroad or online classes. Their perseverance and their closeness to God are deeply moving.

Carrying these stories, especially in moments of profound loss or when the limits of help are painfully clear, takes an immense emotional toll. For Aya and Nadia, caring for themselves is not optional — it’s essential to sustaining their ability to care for others.

Q: What are the hardest moments in this work, and how do you take care of yourself through them?

Aya: The hardest moments are when we lose a patient. The day one of my patients was martyred, I couldn’t work at all — even losing one person takes a huge emotional toll. When that happened, I cried a lot. I spoke with Dr. Chen and then had a therapy session with one of our clinicians, where I let everything out and processed my connection with the patient.

Nadia: For me, the hardest times are when I feel completely helpless. Patients in Gaza have told me, “I want to die, but I’m afraid of death. I can’t handle this anymore. I can’t even recognise the streets around me.” One said she craved something sweet but couldn’t find any food. It’s heartbreaking — and knowing our help has limits makes it harder. In those moments, Dr. Chen has always checked in. All patient-facing staff on our team are also required to be in therapy, which is covered by Healing for Gaza.

The emotional weight of this work has shaped Aya and Nadia’s understanding of what it means to sustain a clinical mental health programme in a war zone. It’s not just about logistics — it’s about holding together the human and operational threads that make therapy possible, even in the most fragile contexts.

Q: From your perspective, what do you wish more people understood about clinical coordination, and what has surprised you most in this work?

Nadia: Clinical coordination is the foundation of our work — if something goes wrong here, the whole chain is affected. Without our team, this care wouldn’t be possible. One of the biggest challenges is encouraging people to start therapy, especially if they’re unsure it will help. We build trust, answer questions, and reassure them — and it’s rewarding when those same patients later say it’s the highlight of their week.

Mental health is a basic need, not a luxury. In the Arab world, therapy once carried stigma, but that’s changing. Without it, some patients might truly lose their sense of self because they have no outlet for the weight they carry. I’ve been surprised by how much Palestinians value mental health care — and how eager they are for it. The growth of Healing for Gaza, and the care with which every detail is managed, has impressed me deeply.

Aya: I’d go as far as saying clinical coordination is the most important part of Healing for Gaza because we’re the link between patients, clinicians, and interpreters — we make sessions happen. I’ve been moved by how quickly patients build trust, often saying their clinicians and interpreters feel like family. For them, therapy is about more than treatment — it’s about connection, trust, and feeling truly seen.

“I’ve been moved by how quickly patients build trust, often saying their clinicians and interpreters feel like family. For them, therapy is about more than treatment — it’s about connection, trust, and feeling truly seen.”

— Aya Zakaria

_____

Heidi Ho is pursuing degrees in public health and journalism at Northeastern University. She is driven by a passion for social justice, health, and science. She previously worked with a non-profit organization in Ecuador and currently writes for multiple publications. Heidi currently serves as a communications intern with Healing for Gaza.